After years of being left for dead, SQL today is making a comeback. How come? And what effect will this have on the data community?

(Update: #1 on Hacker News! Read the discussion here.)

(Update 2: TimescaleDB is hiring! Open positions in Engineering, Marketing, and Sales. Interested?)

Since the dawn of computing, we have been collecting exponentially growing amounts of data, constantly asking more from our data storage, processing, and analysis technology. In the past decade, this caused software developers to cast aside SQL as a relic that couldn’t scale with these growing data volumes, leading to the rise of NoSQL: MapReduce and Bigtable, Cassandra, MongoDB, and more.

Yet today SQL is resurging. All of the major cloud providers now offer popular managed relational database services: e.g., Amazon RDS, Google Cloud SQL, Azure Database for PostgreSQL (Azure launched just this year). In Amazon’s own words, its PostgreSQL- and MySQL-compatible database Aurora database product has been the “fastest growing service in the history of AWS”. SQL interfaces on top of Hadoop and Spark continue to thrive. And just last month, Kafka launched SQL support. Your humble authors themselves are developers of a new time-series database that fully embraces SQL.

In this post we examine why the pendulum today is swinging back to SQL, and what this means for the future of the data engineering and analysis community.

Part 1: A New Hope

To understand why SQL is making a comeback, let’s start with why it was designed in the first place.

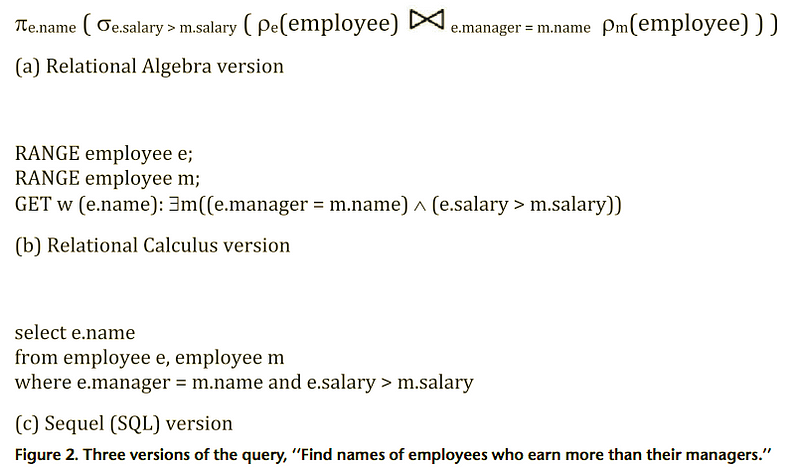

Our story starts at IBM Research in the early 1970s, where the relational database was born. At that time, query languages relied on complex mathematical logic and notation. Two newly minted PhDs, Donald Chamberlin and Raymond Boyce, were impressed by the relational data model but saw that the query language would be a major bottleneck to adoption. They set out to design a new query language that would be (in their own words): “more accessible to users without formal training in mathematics or computer programming.”

Think about this. Way before the Internet, before the Personal Computer, when the programming language C was first being introduced to the world, two young computer scientists realized that, “much of the success of the computer industry depends on developing a class of users other than trained computer specialists.” They wanted a query language that was as easy to read as English, and that would also encompass database administration and manipulation.

The result was SQL, first introduced to the world in 1974. Over the next few decades, SQL would prove to be immensely popular. As relational databases like System R, Ingres, DB2, Oracle, SQL Server, PostgreSQL, MySQL (and more) took over the software industry, SQL became established as the preeminent language for interacting with a database, and became the lingua franca for an increasingly crowded and competitive ecosystem.

(Sadly, Raymond Boyce never had a chance to witness SQL’s success. He died of a brain aneurysm 1 month after giving one of the earliest SQL presentations, just 26 years of age, leaving behind a wife and young daughter.)

For a while, it seemed like SQL had successfully fulfilled its mission. But then the Internet happened.

Part 2: NoSQL Strikes Back

While Chamberlin and Boyce were developing SQL, what they didn’t realize is that a second group of engineers in California were working on another budding project that would later widely proliferate and threaten SQL’s existence. That project was ARPANET, and on October 29, 1969, it was born.

But SQL was actually fine until another engineer showed up and invented the World Wide Web, in 1989.

Like a weed, the Internet and Web flourished, massively disrupting our world in countless ways, but for the data community it created one particular headache: new sources generating data at much higher volumes and velocities than before.

As the Internet continued to grow and grow, the software community found that the relational databases of that time couldn’t handle this new load. There was a disturbance in the force, as if a million databases cried out and were suddenly overloaded.

Then two new Internet giants made breakthroughs, and developed their own distributed non-relational systems to help with this new onslaught of data: MapReduce (published 2004) and Bigtable (published 2006) by Google, and Dynamo (published 2007) by Amazon. These seminal papers led to even more non-relational databases, including Hadoop (based on the MapReduce paper, 2006), Cassandra (heavily inspired by both the Bigtable and Dynamo papers, 2008) and MongoDB (2009). Because these were new systems largely written from scratch, they also eschewed SQL, leading to the rise of the NoSQL movement.

And boy did the software developer community eat up NoSQL, embracing it arguably much more broadly than the original Google/Amazon authors intended. It’s easy to understand why: NoSQL was new and shiny; it promised scale and power; it seemed like the fast path to engineering success. But then the problems started appearing.

Developers soon found that not having SQL was actually quite limiting. Each NoSQL database offered its own unique query language, which meant: more languages to learn (and to teach to your coworkers); increased difficulty in connecting these databases to applications, leading to tons of brittle glue code; a lack of a third party ecosystem, requiring companies to develop their own operational and visualization tools.

These NoSQL languages, being new, were also not fully developed. For example, there had been years of work in relational databases to add necessary features to SQL (e.g., JOINs); the immaturity of NoSQL languages meant more complexity was needed at the application level. The lack of JOINs also led to denormalization, which led to data bloat and rigidity.

Some NoSQL databases added their own “SQL-like” query languages, like Cassandra’s CQL. But this often made the problem worse. Using an interface that is almost identical to something more common actually created more mental friction: engineers didn’t know what was supported and what wasn’t.

Some in the community saw the problems with NoSQL early on (e.g., DeWitt and Stonebraker in 2008). Over time, through hard-earned scars of personal experience, more and more software developers joined them.

Part 3: Return of the SQL

Initially seduced by the dark side, the software community began to see the light and come back to SQL.

First came the SQL interfaces on top of Hadoop (and later, Spark), leading the industry to “back-cronym” NoSQL to “Not Only SQL” (yeah, nice try).

Then came the rise of NewSQL: new scalable databases that fully embraced SQL. H-Store (published 2008) from MIT and Brown researchers was one of the first scale-out OLTP databases. Google again led the way for a geo-replicated SQL-interfaced database with their first Spanner paper (published 2012) (whose authors include the original MapReduce authors), followed by other pioneers like CockroachDB (2014).

At the same time, the PostgreSQL community began to revive, adding critical improvements like a JSON datatype (2012), and a potpourri of new features in PostgreSQL 10: better native support for partitioning and replication, full text search support for JSON, and more (release slated for later this year). Other companies like CitusDB (2016) and yours truly (TimescaleDB, released this year) found new ways to scale PostgreSQL for specialized data workloads.

In fact, our journey developing TimescaleDB closely mirrors the path the industry has taken. Early internal versions of TimescaleDB featured our own SQL-like query language called “ioQL.” Yes, we too were tempted by the dark side: building our own query language felt powerful. But while it seemed like the easy path, we soon realized that we’d have to do a lot more work: e.g., deciding syntax, building various connectors, educating users, etc. We also found ourselves constantly looking up the proper syntax to queries that we could already express in SQL, for a query language we had written ourselves!

One day we realized that building our own query language made no sense. That the key was to embrace SQL. And that was one of the best design decisions we have made. Immediately a whole new world opened up. Today, even though we are just a 5 month old database, our users can use us in production and get all kinds of wonderful things out of the box: visualization tools (Tableau), connectors to common ORMs, a variety of tooling and backup options, an abundance of tutorials and syntax explanations online, etc.

But don’t take our word for it. Take Google’s.

Google has clearly been on the leading edge of data engineering and infrastructure for over a decade now. It behooves us to pay close attention to what they are doing.

Take a look at Google’s second major Spanner paper, released just four months ago (Spanner: Becoming a SQL System, May 2017), and you’ll find that it bolsters our independent findings.

For example, Google began building on top of Bigtable, but then found that the lack of SQL created problems (emphasis in all quotes below ours):

“While these systems provided some of the benefits of a database system, they lacked many traditional database features that application developers often rely on. A key example is a robust query language, meaning that developers had to write complex code to process and aggregate the data in their applications. As a result, we decided to turn Spanner into a full featured SQL system, with query execution tightly integrated with the other architectural features of Spanner (such as strong consistency and global replication).”

Later in the paper they further capture the rationale for their transition from NoSQL to SQL:

The original API of Spanner provided NoSQL methods for point lookups and range scans of individual and interleaved tables. While NoSQL methods provided a simple path to launching Spanner, and continue to be useful in simple retrieval scenarios, SQL has provided significant additional value in expressing more complex data access patterns and pushing computation to the data.

The paper also describes how the adoption of SQL doesn’t stop at Spanner, but actually extends across the rest of Google, where multiple systems today share a common SQL dialect:

Spanner’s SQL engine shares a common SQL dialect, called “Standard SQL”, with several other systems at Google including internal systems such as F1 and Dremel (among others), and external systems such as BigQuery…

For users within Google, this lowers the barrier of working across the systems. A developer or data analyst who writes SQL against a Spanner database can transfer their understanding of the language to Dremel without concern over subtle differences in syntax, NULL handling, etc.

The success of this approach speaks for itself. Spanner is already the “source of truth” for major Google systems, including AdWords and Google Play, while “Potential Cloud customers are overwhelmingly interested in using SQL.”

Considering that Google helped initiate the NoSQL movement in the first place, it is quite remarkable that it is embracing SQL today. (Leading some to recently wonder: “Did Google Send the Big Data Industry on a 10 Year Head Fake?”.)

What this means for the future of data: SQL as the universal interface

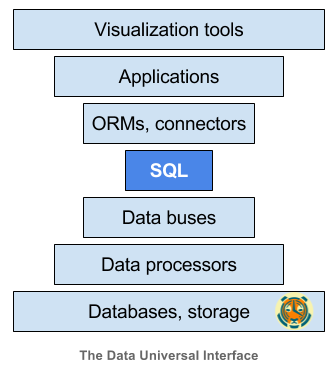

In computer networking, there is a concept called the “narrow waist,” describing a universal interface.

This idea emerged to solve a key problem: On any given networked device, imagine a stack, with layers of hardware at the bottom and layers of software on top. There can exist a variety of networking hardware; similarly there can exist a variety of software and applications. One needs a way to ensure that no matter the hardware, the software can still connect to the network; and no matter the software, that the networking hardware knows how to handle the network requests.

In networking, the role of the universal interface is played by Internet Protocol (IP), acting as a connecting layer between lower-level networking protocols designed for local-area network, and higher-level application and transport protocols. (Here’s one nice explanation.) And (in a broad oversimplification), this universal interface became the lingua franca for computers, enabling networks to interconnect, devices to communicate, and this “network of networks” to grow into today’s rich and varied Internet.

We believe that SQL has become the universal interface for data analysis.

We live in an era where data is becoming “the world’s most valuable resource” (The Economist, May 2017). As a result, we have seen a Cambrian explosion of specialized databases (OLAP, time-series, document, graph, etc.), data processing tools (Hadoop, Spark, Flink), data buses (Kafka, RabbitMQ), etc. We also have more applications that need to rely on this data infrastructure, whether third-party data visualization tools (Tableau, Grafana, PowerBI, Superset), web frameworks (Rails, Django) or custom-built data-driven applications.

Like networking we have a complex stack, with infrastructure on the bottom and applications on top. Typically, we end up writing a lot of glue code to make this stack work. But glue code can be brittle: it needs to be maintained and tended to.

What we need is an interface that allows pieces of this stack to communicate with one another. Ideally something already standardized in the industry. Something that would allow us to swap in/out various layers with minimal friction.

That is the power of SQL. Like IP, SQL is a universal interface.

But SQL is in fact much more than IP. Because data also gets analyzed by humans. And true to the purpose that SQL’s creators initially assigned to it, SQL is readable.

Is SQL perfect? No, but it is the language that most of us in the community know. And while there are already engineers out there working on a more natural language oriented interface, what will those systems then connect to? SQL.

So there is another layer at the very top of the stack. And that layer is us.

SQL is Back

SQL is back. Not just because writing glue code to kludge together NoSQL tools is annoying. Not just because retraining workforces to learn a myriad of new languages is hard. Not just because standards can be a good thing.

But also because the world is filled with data. It surrounds us, binds us. At first, we relied on our human senses and sensory nervous systems to process it. Now our software and hardware systems are also getting smart enough to help us. And as we collect more and more data to make better sense of our world, the complexity of our systems to store, process, analyze, and visualize that data will only continue to grow as well.

Either we can live in a world of brittle systems and a million interfaces. Or we can continue to embrace SQL. And restore balance to the force.

And if you’d like to learn more about TimescaleDB, please check out our GitHub(stars always appreciated), and please let us know how we can help.

Suggested reading for those who’d like to learn more about the history of databases (aka syllabus for the future TimescaleDB Intro to Databases Class):

- A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks (IBM Research, 1970)

- SEQUEL: A Structured English Query Language (IBM Research, 1974)

- System R: Relational Approach to Database Management (IBM Research, 1976)

- MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters (Google, 2004)

- C-Store: A Column-oriented DBMS (MIT, others, 2005)

- Bigtable: A Distributed Storage System for Structured Data (Google, 2006)

- Dynamo: Amazon’s Highly Available Key-value Store (Amazon, 2007)

- MapReduce: A major step backwards (DeWitt, Stonebreaker, 2008)

- H-Store: A High-Performance, Distributed Main Memory Transaction Processing System (MIT, Brown, others, 2008)

- Spark: Cluster Computing with Working Sets (UC Berkeley, 2010)

- Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database (Google, 2012)

- Early History of SQL (Chamberlin, 2012)

- How the Internet was Born (Hines, 2015)

- Spanner: Becoming a SQL System (Google, 2017)