The freeCodeCamp open source community runs Medium’s largest technical publication. Each week, we publish more than a dozen stories on development, design, and data science.

For the longest time, I served as the publication’s sole editor. I edited and published more than 1,200 submissions. But we have always received way more high-quality story submissions than I had time to publish. So I finally admitted to myself that I needed help.

Even though freeCodeCamp reaches millions of people each month through Medium, YouTube, and our coding platform, we’re a small donor-supported nonprofit. We lack the resources to hire professional editors.

This said, a lack of resources hasn’t stopped us in other areas. We have thousands of volunteers running local study groups, contributing to open source projects, and moderating forums and chatrooms.

So in early July, I published a call for volunteer editors. More than 50 people responded. And from those respondents, I assembled and trained a small team of editors.

At the same time, I drafted what would ultimately become this Editor Handbook. This is our guide to how our volunteer editor team edits stories. And in the spirit of transparency, I’m making this public.

You may find this helpful if you edit a technical journal or Medium publication. Or — if you’re one of the 500+ writers who’ve been published in the freeCodeCamp publication — you may just be curious what goes on behind the scenes.

Either way, I hope you’ll find this living document to be interesting and helpful.

How we evaluate, edit, and publish stories

We receive dozens of submissions each week, and are protective of our readers’ time. We seek to only publish stories that are:

- well-written

- relevant to our audience of developers, designers, and data scientists

- factual, and not primarily written to hype up a product or company

The reality of publishing articles in the 21st century

People are busy. They have never been busier. And things will get worse before they get better.

We must optimize for our readers’ scarce time.

In traditional news journalism, that means using the Inverted Pyramid — putting the most important facts first, and adding additional facts in descending order of importance. This way, if someone stops reading, they will still walk away with the main idea and as many important facts as possible.

Most Medium stories more closely resemble feature stories. They recount events (project postmortems, reports on getting a job), or argue a point (exposing security vulnerabilities, endorsing the use of a particular library for a specific purpose).

Yet another category is tutorials. These can be on everything from how to fix a detached head in Git, to how to build a serverless Alexa skill.

Regardless of the type of story — news, feature, tutorial — they should all strive for the same virtues:

- Substance. The story should bring something meaningful to the table. A writer’s story about the Commodore 64 their parents bought for them in the 1980s might be of great interest to them personally, but will it be relevant to a typical reader? Will they walk away with something useful? On the other hand, pretty much all of our readers would benefit from learning more about the job interview process, or gaining a better understanding of how CSS works.

- Accessibility. The story should be as easy for a layperson to understand as possible. There are practical limits to how simple an explanation of a mathematical concept can be, but few writers even begin to approach such limits. A thoughtful communicator can channel their inner Einstein or Feynman and make many complicated concepts relatively easy to understand. But this does take effort.

- Brevity. People are busy. A story should be as short as possible, but no shorter. We can often trim fat without sacrificing much in the way of meaning. We publish plenty of longer stories, like my story on the history of the open internet. I spent 3 months researching it, and it was originally going to be a book, but I was able to cut it down to the point that I could express it in a 26-minute read. Maybe there’s room to cut it down even further.

Again, all of these virtues stem from the reality of our modern age: people are busy.

If people weren’t busy, they might be more interested in reading a nostalgic piece about a someone’s first Commodore 64. They might be willing to struggle through a few undergraduate text books so they could understand someone’s jargon-filled treatise on cloud computing. They might make time to read a meandering tome of an article instead of its cliff notes. But most people are too busy for this.

Everything we do as editors is informed by this basic fact. So I’ll say it again. People are busy.

Tools for getting the interest of busy people

We only have two tools against the relentless scroll of news feeds: a headline and an image.

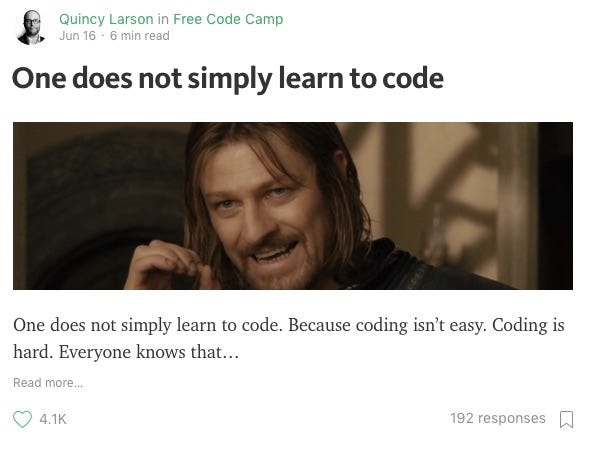

Here’s what a story looks like in Medium’s news feed:

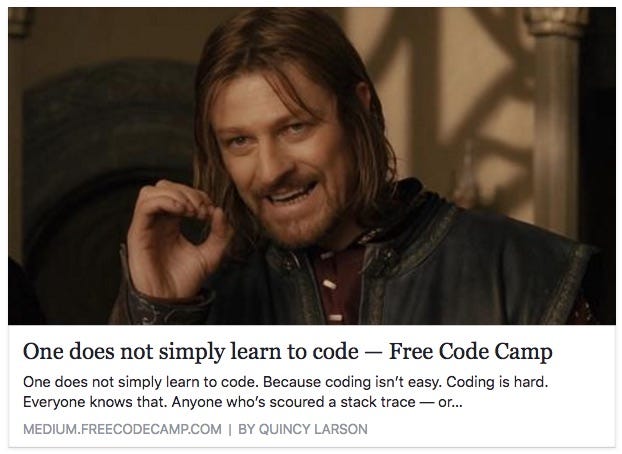

Here’s what it looks like on Facebook:

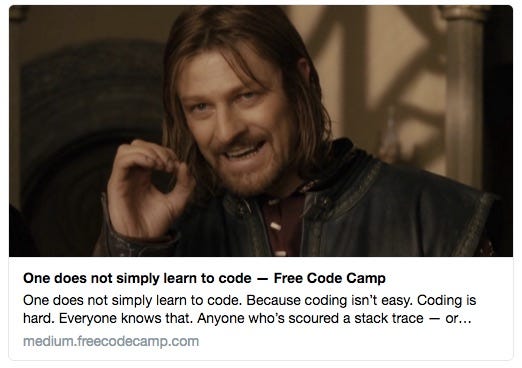

And here’s what it looks like on Twitter:

The headline and opening image are the only things people have to judge a story on. Before they can even read the story’s first paragraph, they must answer a question. It’s the same question that we all ask ourselves every day: is this going to be worth my time?

Your first job as an editor is to choose a headline and image that will make readers — busy people scrolling through their Reddit or their Facebook news feeds — answer “yes.”

A good headline makes all the difference

The headline is the most important part of the story. Spend time refining it.

Don’t use curiosity gap clickbait: “You won’t believe this one ridiculously effective headline dark pattern.”

Don’t use listicle headlines, and generally avoid articles structured as lists: “11 outrageous headlines that will compel people to read your Medium story.” (I am guilty of having written a listacle, and even though it was generally well-received, I still feel it was lazy of me.)

Do tell the truth: “Clever but matter-of-fact headline about an interesting topic.”

How long should headlines be? HubSpot analyzed 6,000 blog posts and found that stories with 8 to 14-word headlines get more social media shares.

This said, make sure the headline is 80 characters or fewer. Otherwise, the title will get truncated in news feeds when people share a story on Facebook and Twitter.

Another consideration is how emotional a headline is. The more emotional (positive or negative) a headline is, the more likely people will click it.

Headlines are traditionally written in “title case.” The Associated Press says to “capitalize the first letter of every word except articles, coordinating conjunctions, and prepositions of three letters or fewer.”

On Medium, I often throw title case out the window and just write headlines like a normal sentence. I even include punctuation as necessary. This format is more conversational, and easier to read.

We don’t generally publish multi-part articles. Labels like “part 1” scare people off, because who knows when you’ll get around to writing part 2. It’s much better to just publish a long, in-depth story, or a series of related but stand-alone articles that can be interlinked by their authors.

Arrest with images

The second most important aspect of a story is its featured image.

Always include at least one image in a story (preferably at the very top). This has the following benefits:

- When people share the story on Facebook and Twitter, it will be more prominent in news feeds, making people more likely to click on it.

- It will look better in Medium’s own news feeds.

- Humans are visual creatures, and click on images.

When publishing a story, Medium lets you choose which image you want to be the story’s featured image. This means the story’s og-image meta property will be this image. This image will serve as the story’s ambassador everywhere: social media news feeds, Reddit, Google News — even RSS readers.

Start considering images early in the editing process. And never publish without at least one image. Otherwise the story will be all but invisible in news feeds.

You should break up long stories with images. To paraphrase Mary Poppins, a spoonful of images helps the text go down.

Medium offers four different image widths. Note that these will all look the same on mobile.

Most of the time, you’ll want to stick with column width:

If you have a chart that is hard to read when it’s small, go bigger:

And if you’re really proud of an image, or if it’s chock full of interesting data, go full-bleed:

… and then there’s side-straddle. Don’t use this size at all, because it makes the text less comfortable to read.

It’s also awkward when you’re done talking about the photo and your text is still pushed to the side.

Yeah. I’m still stuck over here.

If you need to add an image to a story, grab a thematically relevant Creative Commons Zero licensed image from pexels.com. You can use these for free without attribution.

Build momentum with a strong lead

Once the reader clicks through to the story, the trial begins. They’re looking for any excuse to jump back to their news feed. Because reading requires a lot more effort than scrolling through cat photos.

Some writers use intros or updates like “This was published on my blog at [blog URL]” or “Update: this has been posted on Hacker News.” If they’ve added these, you should move these things to the bottom of the story.

Instead, the text should start making points and telling a story immediately.

Help the writer establish their credibility

Figure out a way to establish the writer’s credibility within the first few paragraphs. If they’re a top expert in your field, say so. Don’t assume that people are going to take the time to google them.

“Who you are speaks so loudly I can’t hear what you’re saying.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

Any achievement or distinction that makes people take the writer more seriously will help give readers the impression that “this person knows what they’re talking about.”

For example, if they’re a former Googler/Facebook engineer, or on the core team of a popular open source project, you should find a way to work that in naturally (without it sounding boastful). “Why I left Google to build a personal finance app for kids” sounds a lot more compelling than “I’m building a personal finance app to help kids.”

Reinforce the writer’s credibility throughout the story. They should support their arguments with data. Where necessary, they should use inline links to (non-paywalled) research.

This isn’t the New England Journal of Medicine. This is Medium. So don’t use footnotes. If the writer has used footnotes, figure out a way to work them back into the text, then remove the footnotes at the end of the article. A lot of times, these footnotes aren’t substantial enough to be included, and can just be deleted.

Look and style

Run the text through the Hemingway App. There’s nothing magical about this simple tool, but it will automatically detect widely agreed-upon style issues:

- passive voice

- unnecessary adverbs

- words that have more common equivalents

Adjectives can often be removed by finding more appropriate nouns or verbs.

”I notice that you use plain, simple language, short words and brief sentences. That is the way to write English — it is the modern way and the best way. Stick to it; don’t let fluff and flowers and verbosity creep in. When you catch an adjective, kill it. No, I don’t mean utterly, but kill most of them — then the rest will be valuable. They weaken when they are close together. They give strength when they are wide apart. An adjective habit, or a wordy, diffuse, flowery habit, once fastened upon a person, is as hard to get rid of as any other vice.” — Mark Twain

The Hemingway App will assign a “grade level” for a piece of writing. Even technical stories can pull off a grade level of 6. And they should aspire to.

Most humans are not native English speakers, and the ones who are don’t usually sit around reading Chaucer all day. They want their information accessible and to the point.

Err on the side of breaking long sentences and paragraphs down into shorter ones.

Despite what you may have learned in English composition class, people prefer short paragraphs to “walls of text.”

There’s nothing wrong with single-sentence paragraphs.

Err on the side of creating new paragraphs.

Use contractions. They’ll make prose seem more conversational. That’s always a plus.

freeCodeCamp is an US-based nonprofit, so we’ve chosen to use American English throughout the publication. You may have to change the occasional “analyse” to “analyze” and “colour” to “color.”

Also note that we prefer the metric system to the imperial system.

Spell out the numbers one through ten, then use numerals numbers 11 and above.

When the gender of someone isn’t known — or the author is talking about a hypothetical person they created for the sake of making a point — always use “them,” “their,” and “theirs.” In modern usage, this also functions as a singular third-person pronoun. It’s simpler than saying “he or she.”

Keep tense consistent throughout. If the writer is talking about something that occurred in past, make sure they use past tense.

If you want to emphasize something, use bold, but use it sparingly. Italics are harder to read. Don’t bold hyperlinks — the line underneath them already provides enough emphasis.

Don’t use drop caps. They look elegant in old books, but silly on the web.

Only use one exclamation point at a time, typically only after exclamations like: Golly gee! Hot dog!

Look out for incorrect “smart quotes” like this one: “test“ (note that both the quotes are opening quotes.) Medium doesn’t catch these automatically, so you will need to delete the and retype the quote, at which point Medium should fix it.

Always use double quotes for surrounding quotations and anything that someone might place within “air quotes.” Then use single quotes for quotations within quotations:

“Sometimes when I’m writing Javascript I want to throw up my hands and say ‘this is bulls***!’ but I can never remember what ‘this’ refers to.” — Ben Halpern

Note that I used Medium’s second style of pull quote there, which we use for single-paragraph quotations.

Put commas and periods inside quotes, except when it might confuse a reader (like with variable names or book titles).

In some parts of the world, people put spaces before colons or question marks, like this : example. Don’t do this.

Instead of starting a sentence with “Therefore” start it with “So.”

Instead of starting a sentence with “However” start it with “But.”

Use English instead of Latin:

- Use “for example” instead of “E.G.”

- Use “that is” instead of “I.E.”

- Use “note that” instead of “N.B.”

- Instead of ending lists with “etc.” start them with “like”: “Elvis eats food like bread, peanut butter, and bananas.”

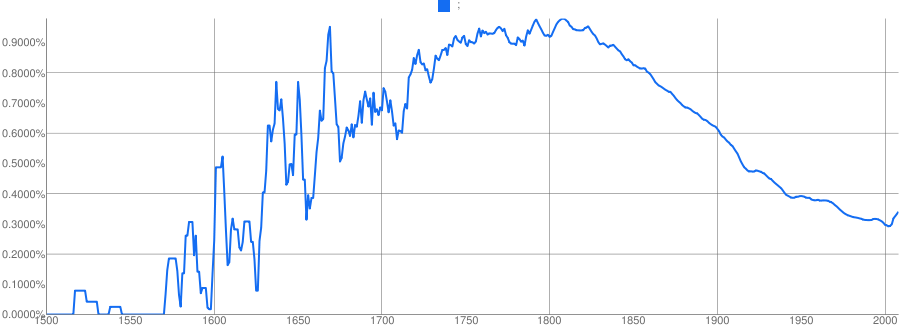

According to Google Books, semicolons have been dying a slow death.

Let’s put them out of their misery. Just use a period instead, and break clauses into separate sentences.

The only place for semicolons in this world is at the end of a line of code.

Use the Oxford Comma when possible. It’s makes things easier, clearer, and prettier to read.

Unlike with code, you should always put punctuation within quotations, like this: the most popular GitHub commit messages are “initial commit,” “update readme.md,” and “update.”

Also, front-end development (adjective form with a dash) is when you’re working on the front end (noun form with no dash). The same goes with the back end, full stack, and many other compound terms.

Showcase code

Where possible, code should be in text form rather than images. This makes the code more accessible to screen readers, and easier for people to copy and paste.

Medium has a hidden shortcut that will turn text plain text like this:

if (developer === true) {

follow(this.mediumPublication);

}

…into a formatted code block:

if (developer === true) {

follow(this.mediumPublication);

}

To accomplish this, select the text, then push:

- Windows: Control + Alt + 6

- Mac: Command + Option + 6

- Linux: Control + Alt + 6

You can also start a code block with triple back-ticks. If you type three backticks («`) on a new line, Medium will switch into code input mode.

To highlight code inline, select it, then press the backtick key. This way, you can format text as code freeCodeCamp() right in the middle of a sentence.

Writers can even embed runnable apps right into Medium. Just in case these don’t render properly in Medium’s mobile apps, we should include links below each of the embeds as a fallback.

Paste a CodePen.io URL into Medium, then hit enter:

View my CodePen here.

You can also do this with JSFiddle.net:

View my JSFiddle here.

Sometimes people start lines of code with a $ if they’re terminal commands. Don’t do this. It will confuse beginners and makes it harder to copy and paste commands. Instead, just say something like “Enter the following commands in your terminal.”

Make links look natural

Figure out a way to work a link into a sentence. One thing I do not recommend doing is putting a link on its own line and pressing enter. This will create a nice looking preview card, like this:

… but readers often assume these are ads, and don’t even look at them.

The only time I would recommend using this is at the end of a story, if you want to link to further reading.

Underlining text makes it harder to read, so only hyperlink a few words.

Don’t paste URLs directly, like this: ❌ https://www.freecodecamp.org ❌

Instead link to sites like freeCodeCamp mid sentence, like I just did here.

Embed media

You can embed Tweets, YouTube videos, and other media by pasting their URLs into Medium on a new line, then pressing enter.

Use these sparingly, since they may distract your reader from finishing your story.

Explain abbreviations

Don’t use an abbreviation unless the abbreviation is more widely understood than what it stands for. For example, HTTP is more widely recognized than Hypertext Transfer Protocol.

If an abbreviation isn’t already widely understood, and you’re going to refer to it more than a few times, you can define it as an abbreviation by doing this:

“Let’s break the code down into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).”

Here I also linked to the Wikipedia article, for readers’ convenience. Don’t assume people will read these external links, though. You still need to define concepts or illustrate them through example.

Avoid defining an abbreviation in your opening paragraphs, as it slows your reader down and makes them less likely to continue reading.

Here’s the very short list of technology abbreviation that you don’t need to define: API, AJAX, BIOS, CPU, CSS, HTML, HTTPS, JSON, LAN, RAM, REST, USB, WWW, XML. For everything else, you should spell it out.

Always spell out short multi-part words like JavaScript and front end. Don’t shorten them. The brevity isn’t worth the possible confusion.

Add 5 tags

Medium allows you to add up to five tags to a story. Use them.

People follow specific topics on Medium. The most popular ones are #tech, #life-lessons, #travel, #design, and #startup.

People who follow the tags you use may see the story in their news feed. Tags also make it easier for people to stumble upon the story in search results.

If a writer chose a tag that isn’t very popular, you can replace it with the more popular variant. For example “JS” is a far less popular tag than “JavaScript.” “UXD” and “UX Design” are far less popular than “UX.”

You should also use as diverse tags as possible (assuming they’re relevant to the article.) For example, an article about Android development doesn’t need “Android,” “AndroidDev,” and “Android Apps.” The readers who are following “AndroidDev” are probably also following “Android” so it’s a waste of precious tag real estate. Instead you can add more popular related tags like “programming” and “technology.”

Acceptable levels of self promotion

Writers write to spread knowledge, but most of them have additional motivations, too.

Some writers are trying to promote their open source project or startup, or publicize the fact that they’re hiring. Some writers are trying to get people to follow them on Twitter, or sign up for their mailing list.

All of these things are fine. But they should be done within reason, and in the footer of the article.

It’s fine for people to cross-post articles from their own blog, but one thing they sometimes do that they shouldn’t is to turn their headline into a link to their blog post. In some cases this may be unintentional, but we should remove that link.

Many writers will also ask for claps at the end of their article. This will help increase the number of people who see the article within Medium’s recommendation system. This is also fine.

Medium recently changed from hearts to claps. But many writers are still asking for hearts. So be sure to change their requests to mention claps instead.

For example, here’s a line you could use: “If you found this article helpful, give me some claps ?.”

Things to look out for as an editor

Plagiarism

Plagiarism — when someone misrepresents someone else’s writing as their own — is a serious offense in academia, and it’s just as serious on Medium. Writers should always attribute quotes to the people who originally said them.

If it’s a multi-line quote, you should use Medium’s pull quotes:

“When you have wit of your own, it’s a pleasure to credit other people for theirs.” ― Criss Jami

If you suspect plagiarism — for example, a paragraph of perfect English in an article that otherwise reads unnaturally, or something that seems exceptionally witty in an otherwise dry article — take the suspicious paragraph and paste it into Google. This is a convenient first line of defense.

If a passage seems to be plagiarized, stop editing. We aren’t going to publish it. Send me an email to let me know. I’ll handle the unpleasant task of giving the author some “real talk” for you.

Gatekeeping

“Gatekeeping is when someone takes it upon themselves to decide who does or does not have access or rights to a community or identity.” — Urban Dictionary

Gatekeeping is a form of elitism, and it runs counter to our principle of accessibility. If you want to get a better understanding of what gatekeeping is, Reddit has a subreddit dedicated to it with some sad (and occasionally, ironic) examples.

A lot of times, writers don’t realize they’re gatekeeping. Here are some expressions they may use:

- obviously

- simply [do something]

- of course [something is such-and-such]

- as everyone knows

- as you’ve probably heard

- [something] is easy

- any [“idiot”, “fool”, “newbie”, “script kiddie”, etc.] can [do something]

If you see gatekeeping, just remove it. Most of these expressions don’t actually add anything to the article.

Discrimination

We have a strict code of conduct that seeks to prevent people from being discriminated against on the basis of “gender, gender identity and expression, age, sexual orientation, disability, physical appearance, body size, race, national origin, or religion (or lack thereof).”

If you see anything that you think represents discrimination, remove it. Not every culture takes these things with the same level of seriousness as Americans do. But if you think it isn’t a misunderstanding, and that the writer is intentionally being discriminative, please bring this to my attention.

Unnecessary profanity

We are widely read by audiences of all ages, so we try not to publish profanity at all.

Mild profanity words like “damn” and expressions like “what the hell” are acceptable.

In most cases, there’s a less-profane alternative to profane phrases that mean the same thing and convey the similar emotions.

Sometimes the f-word is included as an adjective, for example, which is basically unnecessary. People often use the s-word as a synonym for “bad”, and this can also be replaced with something less profane. The expression “BS” basically means “untrue” or “lies.”

We’re a technical publication, so in most cases writing won’t be very heated. When in doubt, you can use **** to replace part of the offending word.

Post-publishing process

After we publish an article, we help publicize it on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. We use Buffer to schedule all these posts, so that they go out at the best possible times.

Before publicizing, we run the articles through Facebook’s debugger and Twitter’s card validator. If they look good and ready to go, we hit the “tweet” icon in the published Medium article, copy the tweet’s text, and load that text into Buffer.

For Twitter posts, we simply remove the quotes around the article title and add a comma after the title (if there’s no other punctuation at the end). If Medium calls the author by their Twitter handle, we leave the “by @username” there. If it just uses their full name, we delete the “by [first name] [last name]” part from the tweet.

For LinkedIn and Facebook posts, we remove the quotes from the title and delete the rest of the text, leaving only the post’s title and the link.

Once we’ve buffered these posts, we consider that article finished.

Conclusion

Thanks for reading this guide. If you have any suggestions for how it can be improved, let me know. Hopefully this guide will grow to include additional editorial considerations and commonly-encountered edge cases.

SOURCE: https://medium.freecodecamp.org/the-freecodecamp-medium-publication-editor-handbook-cb5876d1ef23

Write by

![]()