Inthe recent past, several large players, including Google and Facebook, have released their latest and ultimately disappointing diversity numbers. Even with increased effort and resources poured into diversity hiring programs, Facebook’s headcount for women and people of color hasn’t really increased in the past 3 years. Google’s numbers have looked remarkably similar, and both players have yet to make significant impact in the space, despite a number of initiatives spanning everything from a points system rewarding recruiters for bringing in diverse candidates, to increased funding for tech education, to efforts to hire more diverse candidates in key leadership positions.

Why have gains in diversity hiring been so lackluster across the board?

Facebook justifies these disappointing numbers by citing the ubiquitous pipeline problem, namely that not enough people from underrepresented groups have access to the education and resources they need to be set up for success. And Google’s take appears to be similar, judging from what portion of their diversity-themed, forward-looking investments are focused on education.

In addition to blaming the pipeline, since Facebook’s and Google’s announcements, a growing flurry of conversations have loudly waxed causal about the real reason diversity hiring efforts haven’t worked. These have included everything from how diversity training isn’t sticky enough, to how work environments remain exclusionary and thereby unappealing to diverse candidates, to improper calibration of performance reviews to not accounting for how marginalized groups actually respond to diversity-themed messaging.

While we are excited that more resources are being allocated to education and inclusive workplaces, at interviewing.io, we posit another reason for why diversity hiring initiatives aren’t working. After drawing on data from thousands of technical interviews, it’s become clear to us that technical interviewing is a process whose results are nondeterministic and often arbitrary. We believe that technical interviewing is a broken process for everyone but that the flaws within the system hit underrepresented groups the hardest… because they haven’t had the chance to internalize just how much of technical interviewing is a numbers game. Getting a few interview invites here and there through increased diversity initiatives isn’t enough. It’s a beginning, but it’s not enough. It takes a lot of interviews to get used to the process and the format and to understand that the stuff you do in technical interviews isn’t actually the stuff you do at work every day. And it takes people in your social circle all going through the same experience, screwing up interviews here and there, and getting back on the horse to realize that poor performance in one interview isn’t predictive of whether you’ll be a good engineer.

A brief history of technical interviewing

A definitive work on the history of technical interviewing was surprisingly hard to find, but I was able to piece together a narrative by scouring books like How Would You Move Mount Fuji, Programming Interviews Exposed, and the bounty of the internets. The story goes something like this.

Technical interviewing has its roots as far back as 1950s Palo Alto, at Shockley Semiconductor Laboratories. Shockley’s interviewing methodology came out of a need to separate the innovative, rapidly moving, Cold War-fueled tech space from hiring approaches taken in more traditionally established, skills-based assembly-line based industry. And so, he relied on questions that could gauge analytical ability, intellect, and potential quickly. One canonical question in this category has to do with coins. You have 8 identical-looking coins, except one is lighter than the rest. Figure out which one it is with just two weighings on a pan balance.

The techniques that Shockley developed were adapted by Microsoft during the 90s, as the first dot-com boom spurred an explosion in tech hiring. As with the constraints imposed by both the volume and the high analytical/adaptability bar imposed by Shockley, Microsoft, too, needed to vet people quickly for potential — as software engineering became increasingly complex over the course of the dot-com boom, it was no longer possible to have a few centralized “master programmers” manage the design and then delegate away the minutiae. Even rank and file developers needed to be able to produce under a variety of rapidly evolving conditions, where just mastery of specific skills wasn’t enough.

The puzzle format, in particular, was easy to standardize because individual hiring managers didn’t have to come up with their own interview questions, and a company could quickly build up its own interchangeable question repository.

This mentality also applied to the interview process itself — rather than having individual teams run their own processes and pipelines, it made much more sense to standardize things. This way, in addition to questions, you could effectively plug and play the interviewers themselves — any interviewer within your org could be quickly trained up and assigned to speak with any candidate, independent of prospective team.

Puzzle questions were a good solution for this era for a different reason. Collaborative editing of documents didn’t become a thing until Google Docs’ launch in 2007. Without that capability, writing code in a phone interview was untenable — if you’ve ever tried to talk someone through how to code something up without at least a shared piece of paper in front of you, you know how painful it can be. In the absence of being able to write code in front of someone, the puzzle question was a decent proxy. Technology marched on, however, and its evolution made it possible to move from the proxy of puzzles to more concrete, coding-based interview questions. Around the same time, Google itself publicly overturned the efficacy of puzzle questions.

So where does this leave us? Technical interviews are moving in the direction of more concreteness, but they are still very much a proxy for the day-to-day work that a software engineer actually does. The hope was that the proxy would be decent enough, but it was always understood that that’s what they were and that the cost-benefit of relying on a proxy worked out in cases where problem solving trumped specific skills and where the need for scale trumped everything else.

As it happens, elevating problem-solving ability and the need for a scalable process are both eminently reasonable motivations. But here’s the unfortunate part: the second reason, namely the need for scalability, doesn’t apply in most cases. Very few companies are large enough to need plug and play interviewers. But coming up with interview questions and processes is really hard, so despite their differing needs, smaller companies often take their cues from the larger players, not realizing that companies like Google are successful at hiring because the work they do attracts an assembly line of smart, capable people… and that their success at hiring is often despite their hiring process and not because of it. So you end up with a de facto interviewing cargo cult, where smaller players blindly mimic the actions of their large counterparts and blindly hope for the same results.

The worst part is that these results may not even be repeatable… for anyone. To show you what I mean, I’ll talk a bit about some data we collected at interviewing.io.

Technical interviewing is broken for everybody

Interview outcomes are kind of arbitrary

interviewing.io is a platform where people can practice technical interviewing anonymously and, in the process, find jobs. Interviewers and interviewees meet in a collaborative coding environment and jump right into a technical interview question. After each interview, both sides rate one another, and interviewers rate interviewees on their technical ability. And the same interviewee can do multiple interviews, each of which is with a different interviewer and/or different company, and this opens the door for some interesting and somewhat controlled comparative analysis.

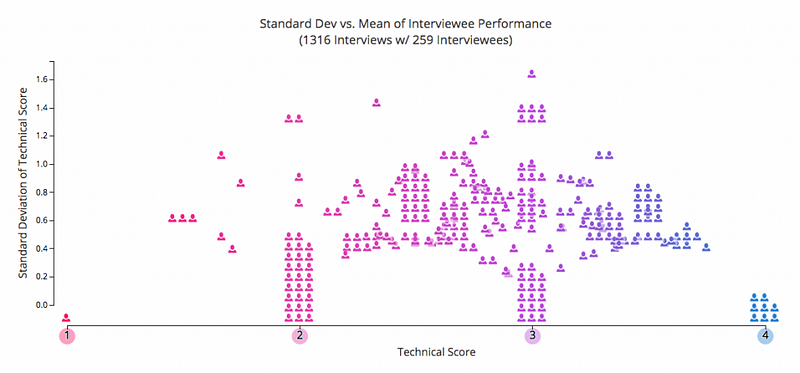

We were curious to see how consistent the same interviewee’s performance was from interview to interview, so we dug into our data. After looking at thousands of interviews on the platform, we’ve discovered something alarming: interviewee performance from interview to interview varied quite a bit, even for people with a high average performance. In the graph below, every person icon represents the mean technical score for an individual interviewee who has done 2 or more interviews on interviewing.io. The y-axis is standard deviation of performance, so the higher up you go, the more volatile interview performance becomes.

As you can see, roughly 25% of interviewees are consistent in their performance, but the rest are all over the place. And over a third of people with a high mean (>=3) technical performance bombed at least one interview.

Despite the noise, from the graph above, you can make some guesses about which people you’d want to interview. However, keep in mind that each person above represents a mean. Let’s pretend that, instead, you had to make a decision based on just one data point. That’s where things get dicey. Looking at this data, it’s not hard to see why technical interviewing is often perceived as a game. And, unfortunately, it’s a game where people often can’t tell how they’re doing.

No one can tell how they’re doing

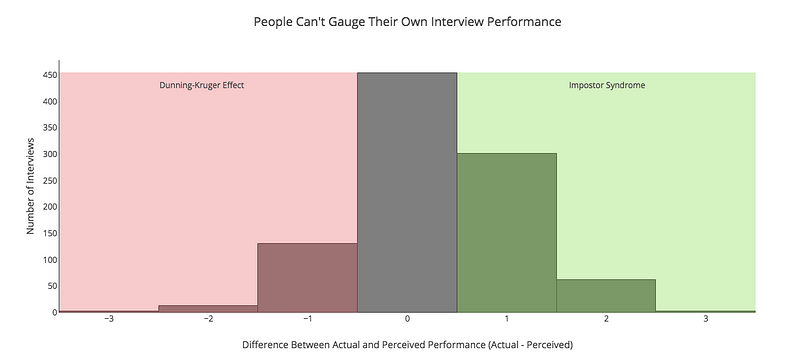

I mentioned above that on interviewing.io, we collect post-interview feedback. In addition to asking interviewers how their candidates did, we also ask interviewees how they think they did. Comparing those numbers for each interview showed us something really surprising: people are terrible at gauging their own interview performance, and impostor syndrome is particularly prevalent. In fact, people underestimate their performance over twice as often as they overestimate it. Take a look at the graph below to see what I mean:

Note that, in our data, impostor syndrome knows no gender or pedigree — it hits engineers on our platform across the board, regardless of who they are or where they come from.

Now here’s the messed up part. During the feedback step that happens after each interview, we ask interviewees if they’d want to work with their interviewer. As it turns out, there’s a very strong relationship between whether people think they did well and whether they would indeed want to work with the interviewer — when people think they did poorly, even if they actually didn’t, they may be a lot less likely to want to work with you. And, by extension, it means that in every interview cycle, some portion of interviewees are losing interest in joining your company just because they didn’t think they did well, despite the fact that they actually did.

As a result, companies are losing candidates from all walks of life because of a fundamental flaw in the process.

Poor performances hit marginalized groups the hardest

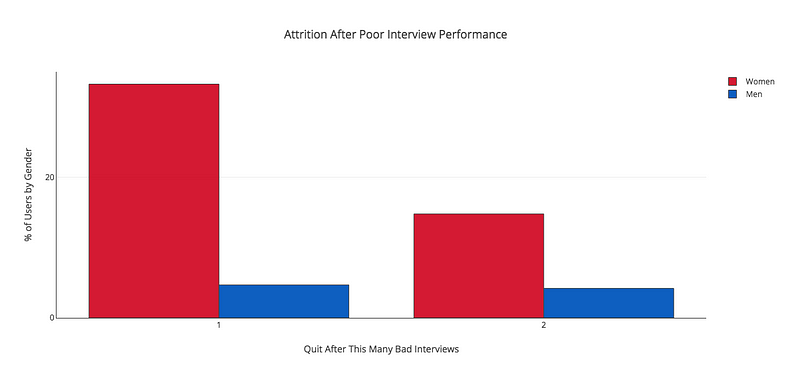

Though impostor syndrome appears to hit engineers from all walks of life, we’ve found that women get hit the hardest in the face of an actually poor performance. As we learned above, poor performances in technical interviewing happen to most people, even people who are generally very strong. However, when we looked at our data, we discovered that after a poor performance, women are 7 times more likely to stop practicing than men:

A bevy of research appears to support confidence-based attrition as a very real cause for women departing from STEM fields, but I would expect that the implications of the attrition we witnessed extend beyond women to underrepresented groups, across the board.

What the real problem is

At the end of the day, because technical interviewing is indeed a game, like all games, it takes practice to improve. However, unless you’ve been socialized to expect and be prepared for the game-like aspect of the experience, it’s not something that you can necessarily intuit. And if you go into your interviews expecting them to be indicative of your aptitude at the job, which is, at the outset, not an unreasonable assumption, you will be crushed the first time you crash and burn. But the process isn’t a great or predictable indicator of your aptitude. And on top of that, you likely can’t tell how you’re doing even when you do well.

These are issues that everyone who’s gone through the technical interviewing gauntlet has grappled with. But not everyone has the wherewithal or social support to realize that the process is imperfect and to stick with it. And the less people like you are involved, whether it’s because they’re not the same color as you or the same gender or because not a lot of people at your school study computer science or because you’re a dropout or for any number of other reasons, the less support or insider knowledge or 10,000 foot view of the situation you’ll have. Full stop.

Inclusion and education isn’t enough

To help remedy the lack of diversity in its headcount, Facebook has committed to three actionable steps on varying time frames. The first step revolves around creating a more inclusive interview/work environment for existing candidates. The other two are focused on addressing the perceived pipeline problem in tech:

- Short Term: Building a Diverse Slate of Candidates and an Inclusive Working Environment

- Medium Term: Supporting Students with an Interest in Tech

- Long Term: Creating Opportunity and Access

Indeed, efforts to promote inclusiveness and increased funding for education are extremely noble, especially in the face of potentially not being able to see results for years in the case of the latter. However, both take a narrow view of the problem and both continue to funnel candidates into a broken system.

Erica Baker really cuts to the heart of it in her blog post about Twitter hiring a head of D&I:

What irks me the most about this is that no company, Twitter or otherwise, should have a VP of Diversity and Inclusion. When the VP of Engineering… is thinking about hiring goals for the year, they are not going to concern themselves with the goals of the VP of Diversity and Inclusion. They are going to say ‘hiring more engineers is my job, worrying about the diversity of who I hire is the job of the VP of Diversity and Inclusion.’ When the VP of Diversity and Inclusion says ‘your org is looking a little homogenous, do something about it,’ the VP of Engineering won’t prioritize that because the VP of Engineering doesn’t report to the VP of Diversity and Inclusion, so knows there usually isn’t shit the VP of Diversity and Inclusion can do if the Eng org doesn’t see some improvement in diversity.

Indeed, this is sad, but true. When faced with a high-visibility conundrum like diversity hiring, a pragmatic and even reasonable reaction on any company’s part is to make a few high-profile hires and throw money at the problem. Then, it looks like you’re doing something, and spinning up a task force or a department or new set of titles is a lot easier than attempting to uproot the entire status quo.

As such, we end up with a newly minted, well-funded department pumping a ton of resources into feeding people who’ve not yet learned about the interviewing being a game into a broken, nondeterministic machine of a process made further worse by the fact that said process favors confidence and persistence over bona fide ability… and where the link between success in navigating said process and subsequent on-the-job performance is tenuous at best.

How to fix things

In the evolution of the technical interview, we saw a gradual reduction in the need for proxies as companies as the technology to write code together remotely emerged; with its advent, abstract, largely arbitrary puzzle questions could start to be phased out.

What’s the next step? Technology has the power to free us from relying on proxies, so that we can look at each individual as an indicative, unique bundle of performance-based data points. At interviewing.io, we make it possible to move away from proxies by looking at each interviewee as a collection of data points that tell a story, rather than one arbitrary glimpse of something they did once.

But that’s not enough either. Interviews themselves need to continue to evolve. The process itself needs to be repeatable, predictive of aptitude at the actual job, and not a system to be gamed, where a huge benefit is incurred by knowing the rules. And the larger organizations whose processes act as a template for everyone else need to lead the charge. Only then can we really be welcoming to a truly diverse group of candidates.

Want to become awesome at technical interviews and land your next job in the process? Join interviewing.io!

Write by

Aline Lerner

Co-founder of interviewing.io. Hire engineers based on merit, not pedigree.