Let’s talk security today. In our new blog post, we discuss user authorization as one of the basic REST API security aspects. Join the discussion to talk about the pros and cons of the existing approaches to user authorization implementation.

REST is a modern architectural style that defines a new approach to designing web services. Unlike its predecessors, HTTP and SOA, it’s not a protocol (read: a strict set of rules), but rather a number of recommendations and best practices of how web services should communicate to each other. The services that are developed in compliance with the best REST practices are called “RESTful web services.”

Security is a cornerstone of RESTful web services. One of the ways to enable it is a proper in-built user authentication and authorization mechanism.

There are lots of ways to implement user authentication and authorization within the RESTful web services. The main approaches (or standards) we are going to talk about today are the following:

- Basic authentication

- Oauth 2.0

- Oauth 2.0 + JWT

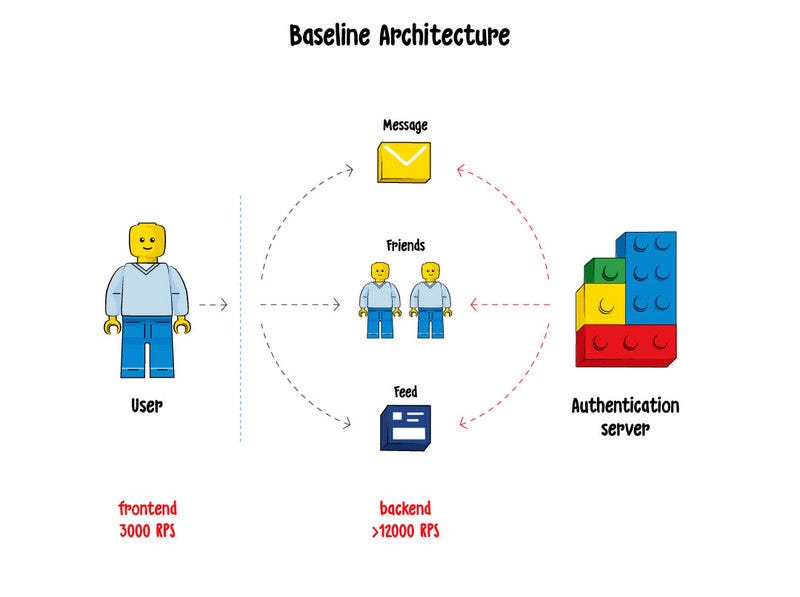

To make our discussion more specific, let’s assume that we have microservices on the backend of our application, and upon each user request, several services at the backend have to be called to collect the requested data. Thus, we will examine each standard not only in terms of security issues, but also in the context of additional traffic and server load they generate. Here we go…

Basic authentication

The oldest and the simplest standard on the list.

How it looks: username + password + Base64 (a basic algorithm of encoding).

How it works: Imagine that a user tries to log into their Facebook account to access feed, messages, friends, and groups, which are all separate services. After the user inserts their username and password, the system knows they are allowed to enter and lets them in. However, it doesn’t know by default what are their roles and privileges, what services they are allowed to access, etc.

So every time the user tries to access any service, the system should once again verify if they are allowed to do this, which implies an additional call to the authentication server. As far as there are four services in our example, there will be four additional calls per user in this case.

Now imagine that we have 3K user requests per second, though in case of Facebook 300K sounds more realistic. Multiplying them by four services, we will end up with 12K calls to the authentication server per second.

Summary: bad scalability, a huge amount of additional traffic that does not bring business value, significant load on the server.

Oauth 2.0

How it looks: username + password + access token + expiration token

How it works: The main idea of the Oauth 2.0 standard is that after a user logs into the system with their username and password, a client (a device the person uses to access the system) receives a pair of tokens, which are an access token and a refresh token.

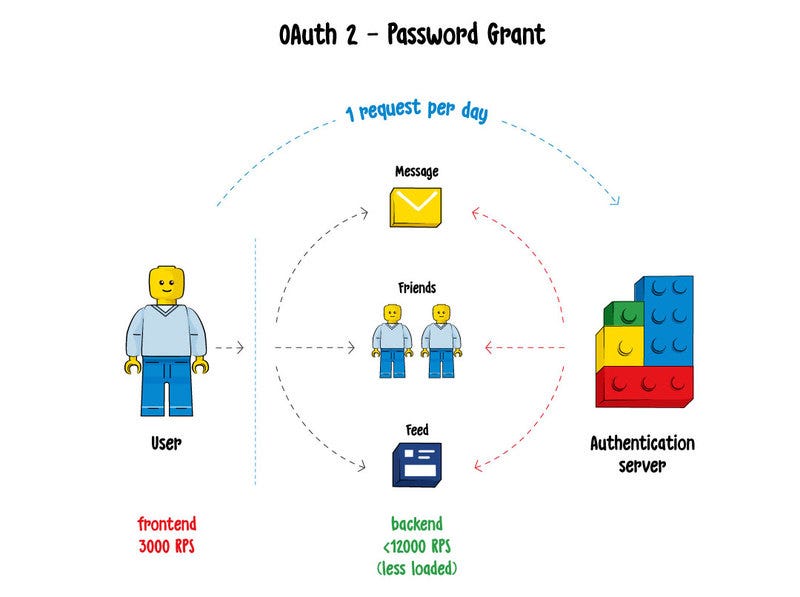

The access token is used to access all services in the system. After it expires, the system uses the refresh token to generate a new pair of tokens. So, if a user enters the system every day, the tokens will also be updated every day, and there will be no need to log into the system with username and password every time. The refresh token also has its expiration period (though it’s much longer than the one of the access token), and if a user hasn’t entered the system for — let’s say — a year, they are likely to be asked to insert the username and password again.

The Oauth 2.0 standard came to replace the basic authentication approach, and it has certain advantages, such as that a user doesn’t have to insert username and password every time they want to enter the system. However, the system still needs to make calls to the auth server, as in the case with the basic auth approach, to check what what the user who owns the token is authorized to do.

Let’s imagine that the expiration date is one day. That implies significantly less load on the login server, because a user has to insert their credentials only once a day, not every time they want to enter the system. However, the system still needs to verify each token and to check out the user roles as well as store state somewhere. So, we again end up with multiple calls to the authentication server.

Summary: same issues as with the basic authentication approach — bad scalability and a huge load on the authentication server.

OAuth 2 + Json Web Tokens

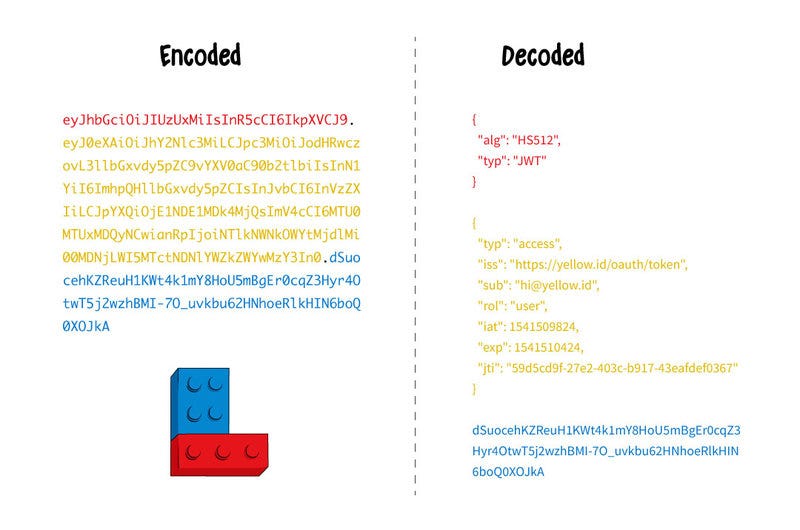

How it looks: username + password + JSON map + Base64 + private key + expiration date

How it works: When a user logs into the system with their username and password for the first time, the system returns back not just an access token, which is simply a string, but a JSON map containing all user information, such as roles and privileges, encoded with Base64 and signed with a private key. This is how it looks with and without encoding:

Looks scary, but this actually works! The main difference is that we can store state in the token, while services stay stateless. This means that the users themselves hold their own info and there is no need for additional calls to retrieve it as everything is already inside the token. And this is a huge deal in reducing the load on the server. This standard is widely used all over the world.

Summary: good scalability, works fine with microservices.

Bonus: Amazon approach

A brand- new, fancy approach, called HTTP signatures. Amazon is one of the big players currently using it.

The main point is that when you create an Amazon account, they generate a permanent and super secret access token, which you should store very carefully and never show to anyone. When you need to request some info from Amazon, you take all http headers, sign them with this private token, and send this string as an additional header.

On the server side, Amazon also has your super private access key. What they do next? They simply take your http headers and sign them with this key. Then, they just compare this string with what you’ve sent as a signature string; if they are identical, then you are really who you said you are.

The great benefit is that you have to send your username and password only once — to receive the token. As for the headers signed with the private key, there is literally no chance to encode them. Even if someone intercepts the message — who cares 😉

Originally published at yellow.id.

Source: https://medium.com/@yellow/rest-security-basics-f59013850c4e

Written by

Yellow

A team of engineers writing about web & mobile applications, here’s how we think (https://yellow.id/blog) and live (https://www.instagram.com/yellow.id/)